Read Part I

As stated in the previous post, I haven’t been able to ascertain whether 1953’s O Cangaceiro represents the absolute ground zero of Cangaco as a film genre, although it can certainly be said that many similar films followed in its path. 1961’s A Morte Comanda O Cangaco sees O Cangaceiro’s Alberto Ruschel and Milton Ribiero once again pitted against one another, this time with Ruschel playing a rancher -- perhaps with a past as a bandit himself (sorry, no English subtitles) -- who goes to war against the vicious band of Cangaceiros lead by Ribiero, who appears to be playing a slightly less nuanced version of the same character he played in O Cangaceiro.

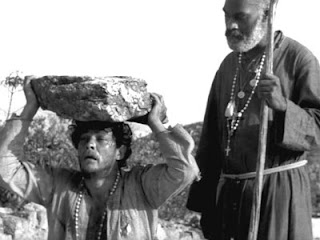

It doesn’t take long to notice that A Morte is a much more violent and action driven film than O Cangaceiro, featuring frequent shootouts, chases, and instances of sweaty hand-to-hand combat. We are even given a glimpse of the gruesome aftermath of a beheading, in a “how bad are they” moment in which Ruschel’s character finds that the gang has stuck his feisty old Grannie’s head on a pike. These elements combine with the film’s bombastic score, endless sunny vistas, and the comparably broad moral line drawn between its heroes and villains to make A Morte seem much more like a traditional American Western than O Cangaceiro. The most identifiably Brazilian aspect of it, as with O Cangaceiro, is the heavy hand of Christianity that hangs over it, exemplified by a very Christ-like holy man who wanders in and out of the narrative in order to give the other players a moment of moral pause.

This is all not to say that A Morte Comanda O Cangaco is not an enjoyable film; as a straightforward shoot-em-up it is, in fact, a finely tuned machine. However, while every bit as technically accomplished as O Cangaceiro, it lacks the tragic element that lent that earlier film its gravity. Nonetheless, it should easily appeal to fans of Hollywood’s Technicolor-hued cowboy epics, and even fans of Spaghetti Westerns.

A Morte director Carlos Coimbra was known in particular for his Cagaceiro films, among which -- in addition to A Morte -- were 1964’s Lampiao, King of the Badlands and 1967’s Cangaceiros de Lampiao, both of which starred the dependably fearsome Ribiero. Coimbra would return to the genre in 1997 for a planned remake of the original O Cangaceiro. Unfortunately, illness would ultimately prevent him from taking the director’s seat, and the film instead had to be finished by Anibal Massaini Neto, with Coimbra credited as production supervisor.

The first, most noticeable departure that Neto’s O Cangaceiro takes from its source material is its use of a framing device by which the story is told from the perspective of Tico, a young boy adopted by the Cangaceiros, who relays the events from his prison cell as an elderly man. The second is how much more explicit and plentiful the film is in its presentation of violence. The branding of the woman, occurring off-screen in the original, is shown in loving detail, while, elsewhere, heads are hacked off with abandon, and a protracted torture scene is crowned with a tongue being graphically cut out. At the same time, Neto spices up the tale’s romantic tensions with a generous apportionment of nudity and simulated sex.

In keeping with this grand guignol tone, actor Paul Gorgulho’s portrayal of Captain Gardino is much more that of your traditional, cackling, homicidal maniac than seen previously. On the other hand, the police -- who are never the good guys in these films -- have their demonic nature bluntly driven home by a gang rape sequence that is bald faced in it prurience. In most other respects, the film follows the template of the original in a fairly literal minded fashion, while failing completely to approach its level of artistry and nuance -- a shortcoming exemplified by the filmmakers’ perceived need to supply an audience surrogate, and an infantilized one at that. In fact, Neto’s unflagging insistence upon orienting our perspective from Tico’s point of view becomes at once both laughable and annoying, with even the most intimate moments requiring a shot of Tico watching surreptitiously from a hiding place in some tree or shrub to set it up.

In the plus column, the film, like the original, features a lot of wonderful music, although the song numbers are less naturalistically integrated into the action and, as a result, often come across as being a bit canned. This, along with the movie’s moments of Telenovela level melodrama, might serve as an obstacle to those who want to enjoy this O Cangaceiro for the energetic piece of misleadingly pedigreed trash cinema that it ultimately is, but I would nonetheless not attempt to discourage them from trying to do so.

All in all, Neto’s take on O Cangaceiro seems to be the endpoint of a long journey that saw the Cangaco genre, from its point of inception, veering increasingly into the realm of exploitation cinema. The concept even received the sexploitation treatment in the mid 70s, with films like Roberto Mauro’s As Cangaceiras Eroticas -- in which a gang of female bandits have their way with their male victims -- and Al Ilha das Cangaceiras Virgens. One notable detour into respectability was 1964’s Deus e o Diablo na Terra do Sol, which was released internationally as Black God, White Devil. Directed by the then 25 year old Glauber Rocha -- who was at the forefront of Brazil’s French New Wave and Italian Neo-Realist inspired Cinema Novo movement -- it is today widely considered to be one of the greatest of all Brazilian films.

Deus begins with a shot of flies feasting on the head of a dead cow, after which we are introduced to Manuel and Rosa (Geraldo Del Rey and Yona Magalhaes), a cowherd and his wife whose life of grinding poverty in the barren Northeast has apparently driven them nearly mad with despair. After Manuel murders a wealthy rancher who was trying to cheat him, the two go on the run, taking shelter among the followers of a charismatic holy man called Sebastian. Rosa watches in dismay as the simple Manuel, desperate for any shred of hope, is seduced by the preacher’s utopian prophecies, eventually becoming so wildly enrapt that he is willing to sacrifice his own newborn son on Sebastian’s altar. Rosa kills Sebastian in a rage, but only moments before the encampment is attacked by a band of mercenaries lead by the famed Cangaceiro hunter Antonio Das Mortes (Mauricio Do Valle), who has been hired by local clergy and business leaders to eliminate the threat to the status quo that Sebastian and his devotees represent. All of the followers are slaughtered, except for Manuel and Rosa, whom Antonio leaves alive to tell the tale.

Manuel and Rosa next fall into the company of Captain Corisco (Othon Bastos), a lone, raving Cangaceiro, who brings with him news of the recent deaths of Lampião and Maria Bonita. Proclaiming that he now houses the spirit of the legendary outlaw within himself, Corisco grandiosely pledges himself to avenging Lampião’s murder. Manuel, having already proven himself easy prey for such charismatic madmen, is quick to throw his lot in with Corisco, and ends up joining him on a senseless campaign of rape, torture and murder. Meanwhile, the forces of Antonio Das Mortes, for whom Corisco is a prize target, close in on the group.

Compared to the Cangaco films previously discussed, Deus e o Diablo na Terra do Sol is art house with a capital “A”. It alternates between long, wordless takes and sudden, jarring transitions, contrasting moments of harsh naturalism against sequences that are self consciously stagey in their composition. As other reviews have mentioned, it’s hard not to see in its mix of grit and surrealism a precursor to Jodorowsky’s El Topo. Yet, while El Topo, if archly, borrows from classic Western iconography in the presentation of its outlaw protagonist, Deus’ version of the Cangaceiro is one coolly stripped of all romantic trappings. For Rocha, a figure like Captain Corisco is as much an exploiter of the poor’s desperation and vulnerability as is a religious opportunist like Sebastian, or the wealthy landowner who attempts to swindle Manuel at the film’s beginning.

The uncompromising bleakness of its vision makes Deus a film that is every bit as difficult as Neto’s retake on O Cangaceiro is nakedly pandering. As a result, it might be hard going for those more predisposed to enjoying the shoot-em-up trappings of those films in the Cangaco genre that I discussed earlier. For myself, I have to say that, while especially prone to the colorful thrills of a crowd-pleaser like A Morte Comanda O Cangaco, I appreciated each of those films, Deus included, on their own markedly varying terms, while at the same time being impressed by their heterogeneity overall.

As always, any additional information that readers can supply on this subject would be greatly appreciated. Groping blindly through the less brightly lit corners of world cinema the way I tend to is a means of endlessly generating new grounds for apology, and there will likely be major holes in the information I’ve related above. After all, my previous exposure to Brazilian films of the vintage of O Cangaceiro and its progeny was limited to the exploits of Coffin Joe. I only ask that those more knowledgeable than myself see my fumblings for the desperate cry for help that they are, take pity, and provide me with whatever information they can so that I may be set on the path toward being, well, at least marginally less ignorant. Believe me, I welcome the journey –- especially if that path is paved with more films as uniquely thrilling as those I’ve attempted to describe.

2 comments:

Todd, I'm just as interested as you for more info about these films, but I gotta say, you wrote a damn fine primer!

Personally, I think I'd enjoy the more arty offerings, but I loved reading about all of the genre's permutations.

BTW, if you ever find out where one can buy one of those cool cangaceiro hats, let me know. ;)

I think for the hat to be truly authentic, you have to make it yourself from the skin of one of your victims.

Post a Comment